Several years ago, I was stranded at the Ollagüe Crossing from Bolivia to Chile.

I had paid a local Bolivian to give me a ride there from one of Bolivia's armpits, Uyuni, a town that is basically a discharge pipe for tourists coming off of the Salt Flats, as I had just done.

The buses in Bolivia weren't running that day, but no one could tell me why.

The Chilean border guard offered this as an explanation: "F'n Bolivians, man, if some saint supposedly made love to a cat on this day, they shut down their entire economy to celebrate it. Happens nearly every other day, you know."

"That's ok," I told him, "I'm just going to hike in and pick up the bus to Callama."

He shook his head no, emphatically.

"No way, man. That's a no-go, now."

The guard looked like a guard. Steadfast but caring less than a military guard might. There was confidence in his recognition of his powerlessness over the chaos that border crossings often are.

"F'n narco shit, man. They keep killing the backpackers like you, so they've closed the trail. Nobody asked me, but I would like to suggest we kill the narcos instead."

This conversation took place in perfect English, the sort I've heard in California all my life.

"But don't worry, man, we'll figure it out. Just hang out for a while. But do me a favor, friend put your knife away. We're not in Bolivia. We're civilized." He laughed as he said it. I took the knife from my belt and put it into my pack.

I left my pack near his station, went to the cafe, and got two sandwiches and Cokes. When I returned, he didn't want the sandwich but took the Coke.

"I was in Texas for a year. That's where I got this girl." He pet his guard dog, trained to search for drugs by the U.S. Government.

"I F'n loved Texas, man. I may have stayed and become a Texan if my wife would have let me."

He explained that running this border crossing was a good job, but he worked three hours away from his family and only went home twice a month.

"It's still closer than Texas.", I offered, and he laughed.

His love for Texas and, by extension, the U.S. makes sense. Geographically, the two countries are strikingly similar. They're both mountainous regions, sharing the same Pacific Ocean, and within the "Ring of Fire," the tectonic belt that causes the ground to shake. The Chilean Capital of Santiago feels like Los Angeles, complete with our Smog. If you drive the highway from Santiago to the ocean at Valparaiso, you'll feel like you're going through California's Central Valley.

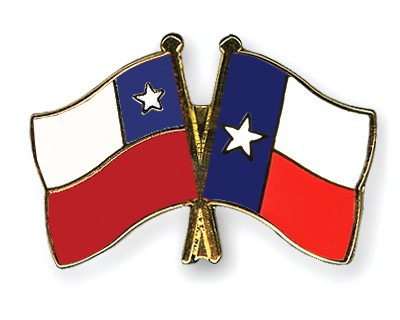

Culturally, Chileans share much in common with Texans. Chile gained independence from Spain in 1810, and Texas became a Republic in 1836. Both share a "Lone Star" flag and an iconoclast mentality.

When I visited Chile, my experience was a welcoming one. Chile is fascinating for many reasons, but a large one is that they relatively recently regained their Democracy. From 1974-1990, the Country was ruled by a military dictatorship, replete with all of the abuse, trauma, and horror that accompany one. That meant for a very long time when you met a Chilean, they understood the loss of freedom and valued it.

Every place has its own unique ways of dealing with the people who visit it. Often, this depends on the identity of the people who live there and their circumstances. There is money, of course; the money brought from tourism can be fuel for the developing world.

There is a snobbery in the world against tourists, likely with good reason. The tourist isn't seeking experience; he is only a voyeur. He travels to some faraway land and does everything he can to insulate himself against the inconveniences of such a journey. The brilliant Anne Tyler wrote in her novel, "The Accidental Tourist," about a travel writer who wrote guides to make travel as unobtrusive as possible, as if you've never left home. So it is with the tourist who returns home with fond memories of our carefully choreographed differences.

But the traveler seeks out the commonalities in the places he visits and the people who live there. At least, that's my aspiration wherever I go.

So I sat with my new and temporary friend, the border guard, who was attempting to find a willing driver to take me to the bus station, and one who probably wouldn't kill me.

We talked about Texas and beer and BBQ. We talked about football and soccer. I explained why soccer was an inferior sport. I shared stories of my adventures around the continent, and he laughed again.

"You're going everywhere I never want to go."

After a few hours, he found someone with a pick-up truck to take me to Chile.

"Chao California."

"Chao Texas"

I handed a few bucks to the driver and hopped in the truck bed with my pack.

The old truck offered up every pothole on the dirt highway called Ruta 21. There was nothing but desolation and dirt, punctuated by the occasional dilapidated house or a church that sat in decay as a colonial remnant.

He dropped me, as promised, at the bus stop about halfway to my next destination, where the road turned in two directions. I was grateful he did not demand money or my kidneys; he only smiled and waved goodbye.

I sat at the wooden bus shelter and ate the second sandwich the guard had declined. I looked across the road at an abandoned mining pit and wondered if the houses in the distance were abandoned, too.

I read a book about a traveler and tried not to fade off to sleep before my bus arrived.

Wonderful catchline! My first thought was my visit to the end of the Berlin Wall, before I knew it tour describing Bolivia to mid state California, brilliant !