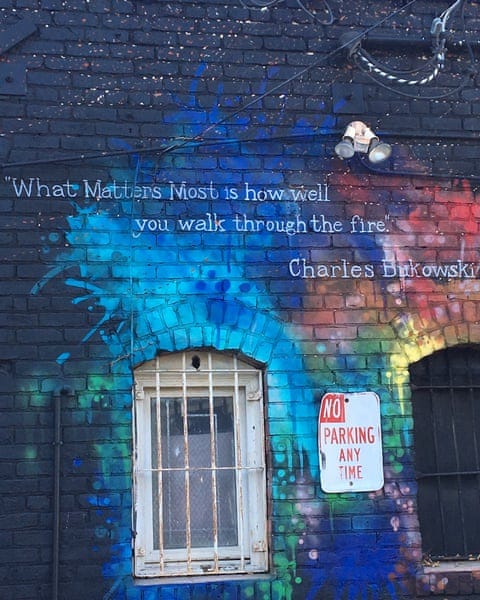

Charles Bukowski was a poet-drunk, a writer, and a misogynist. Some might say. There’s probably nothing left to say about Charles Bukowski that hasn’t already been said. He was canonized in an era long gone and wrote about a City that left with it. He would be canceled today, but his words remain. You will smell cheap beer and blood off the pages if you read him.

Bukowski is a ghost. He died in 1994 and is buried less than a mile away from my Mother’s house. He moved to my hometown of San Pedro sometime around 1978, away from the haunts of East Hollywood and the vice and distraction that brought him fame.

I was in downtown San Pedro early one morning this week and took in all of the new and gleaming buildings filled with people, electric cars, and small dogs. I wonder what he would have thought about the change in the town he adopted. He may have known it would come, he chose the place as a refuge to leave the dark courts of his fiction behind.

When they prune away the old buildings and the old places, and get after the underbrush, there is always a danger of cutting too close to the quick. But cities and people grow tired of being wild, and someone will inevitably want to wash the dirt off.

Bukowski spent most of his life in East Hollywood and Mid-City, in apartments with cockroaches and urine-colored carpets. He wrote about the bars and the women he found there, and all of the other broken things he found there too. He wrote about the grind and dead-end jobs you had to suffer through. His writing about his time with the Post Office always reminds me of T.S. Eliot, who wrote The Waste Land while working as a banker.

Bukowski moved to San Pedro because he was finally making money from writing and needed a tax write-off, so he bought a house on Santa Cruz Street. He wrote a poem about buying the house:

"Everybody's worried about my soul now / I am worried about my soul now."

And now we worry about the soul of our cities. That’s the trick, isn’t it? Are we making things better or just building a new place and stealing our old names? But everybody’s worried, aren’t they? The young are worried about creating a city that’s fit to live in and one they can afford, and the old worry about not getting kicked out of it.

The money people are worried about making it pay, and the politicians are worried about getting paid back. We ask a lot from the places we come from. Sometimes the burden is too great to let the host survive.

Bukowski moved to a port town, a union town. It still is, but it’s different now. Bukowski moved to a place with a working shipyard, plenty of bars that opened at 6 AM, and a port where labor still held the center. He called it “the end of the line," the sort of place you could disappear without completely falling off the map.

His work was about suffering, grit, and grime, and those raw and visceral things that are never sweet and offer no happy endings. But he moved to this port town because it was softer than the places he had come from and held promise for his own future.

He worried about losing the things in himself that many of us worry about losing in our cities. I take no issue with progress. In the dark woods of mid-life, I try to find less and less to take issue with. And now I’m old enough to know that life is a series of tradeoffs.

But you're just left wondering and wandering when you don’t know the cost.

I will hold no nostalgia for broken windows and liquor store robberies if all the gentrified fever dreams come true. We can’t keep our places like mosquitoes suspended in amber and call them authentic. Cities live and breathe and must grow old with us and renew with those who come after us. Otherwise, they become mere relics of the past, as useful as some old rummy in a San Pedro dive bar, drinking himself blind, lying about the prize fights he never won.

The best part about getting old is that we’re no longer required to solve the world’s problems. That’s a young person’s game. We can rest in the contented haze of lamentation.

Cities are best grown organically, not passed through some mystical planning machine that spits out a new place we only remember by its old name. It’s the same with all good things, I suppose. Writing, relationships, parties, and good cooking. The conditions must be just right, and good things might happen. Or they won’t.

I have shared this with you before, but it’s worth revisiting here. If you find yourself in the Port of Los Angeles, you can stop by Bukowski’s grave. You’ll find his name on a bronze plaque, a tiny icon of a boxer, and the words: "Henry Charles Bukowski Jr. / Hank / 1920–1994" — and beneath that, “Don’t Try.”

xAP

Thanks Ante ! Very informative! Still love Pedro nothing like it ! 💯❤️