When I tried to teach my nephew how to box during his Sylvester Stallone phase, he came at me with his arms swinging wildly, chin wide open. I gave him the same advice I had been given: “Pretend you’re fighting in a phone booth.”

He stared at me like I had just spoken a foreign language.

It took a second for the disconnect to register. He had no idea what a phone booth even was. The realization hit like finding a gray hair or buying readers in bulk: the payphone had died, and I hadn’t noticed. His blank stare brought a rush of memory. I remembered payphones not as relics, but as lifelines.

For much of the 20th century, payphones were everywhere. Liquor stores, bus stops, gas stations, and shopping malls all had them. The booths began to disappear first, replaced by glass and aluminum stalls that offered none of the charm and half the privacy. Using a payphone was a biohazard obstacle course: sticky receivers, chewing gum welded to the frame. You hoped the change left over from buying a pack of cloves at 7-Eleven would be enough to call for a ride home. Calls were a nickel once, then a dime, and a quarter by the mid-1980s. If you didn’t have coins, you scraped the return slot with your finger and prayed something slid back out.

Looking back, it seems absurd how much effort it took to make a phone call. No wonder there are only 149 payphones left in Los Angeles today, according to the LA Times.

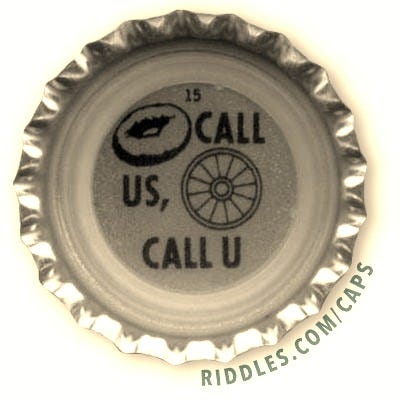

Back in the age of peak payphone, I’d ride my skateboard around the South Bay, using the RTD bus to cover longer distances. Payphones weren’t just background noise. They were checkpoints, little outposts of possibility. I could always find one to call home and maybe spin a story about why I’d be out late. Sometimes I’d drop a quarter to call my cousins and coax them into meeting me at the Vendome Liquor Store to buy a couple of six-packs of Lucky Lager, the stubby bottles with pictogram puzzles under the caps.

When I graduated from the bus to my own car, I got a pager. If a number flashed on its single-line screen, I’d pull over at the nearest payphone to call it back. That little pager screen had a secret language, with codes like 911 or 07734, which spelled “hello” upside down. The pager was, of course, the gateway drug to the cell phone, which would eventually drive the final nail into the payphone’s coffin. As always, we invite the thing in that kills us.

Movies understood the payphone’s power better than most. In The Terminator (1984), set in Los Angeles, a biker is hunched in a booth, begging his wife to pick him up when Schwarzenegger’s T-800 yanks him out mid-sentence, leaving the receiver dangling. You can still hear his wife calling his name through the line. Warren shrugs it off, saying, “That guy’s got a serious attitude problem,” while the Terminator flips through the phone book looking for Sarah Connor.

Artists have also recognized what we’ve lost. Earlier this year, Alexis Wood and Adam Trunell placed stickers on some of the last-standing payphones in L.A., urging strangers to call a toll-free number and “say goodbye before it’s too late.” People picked up the suspect receivers and poured themselves into the void, leaving messages for lost mothers, friends, and lovers. Payphones have always been makeshift confessionals, a place to say what you couldn’t say at home.

They thrived in the age of anonymity. You could be anyone with a quarter, calling anyone else. A kid needing a ride, a runaway, a cop, a dealer. It was all the same call. No metadata. No GPS ping. Just your voice in the air and a small slice of privacy. That was the paradox. You were standing in public, visible to the world, yet wrapped in a sliver of solitude. Everyone could see you, but few could hear you. With their disappearance, one of the last truly democratic spaces disappeared too.

The analog graveyard is full of bus tokens, mixtapes, VHS tapes, and payphones. They’ve all been swept away by the frictionless promise of a faster, more efficient world. But everything we’ve lost has weight. There was a beautiful resistance in the analog, a sensory richness that the digital age has flattened.

When you find yourself using references that the young no longer understand, you’ve hit a milestone. The world is moving on, and maybe you’re fading behind it. When I gave my nephew my phone booth analogy, I wasn’t searching for a deep metaphor. Those payphones were as current to me as smartphones are to him. In the end, I guess it’s best to accept that the human condition is change. Just keep your hands up and stay tight, because the world never stops swinging.

xAP

Great work as always. This brings up so much for me. Phone booth's were always that "third place" where we got things done (work, office, phone booth - no cars yet bc you couldn't make a call!). Every time they appear in movies, it was to deliver an important plot point (mob movies - pre-burner phone) or a laugh (Remember Airplane - when the reporters hit the bank of pay phones:-) Funny to remember fighting in a phone booth - remember how indestructible they were! You couldn't pull the receiver out, dent it, or break the glass. Growing up as a juvenile delinquent in NJ, we used to marvel at the quality of workmanship at Bell Labs.

So true I like to go back to those days ! Nobody talks anymore they are all on there cellphones ! I see people walking driving, eating all on there phones ! So sad